Eileen Gardiner, Honorary Research Fellow at the Centre for Medieval Studies, University of Bristol, writes:

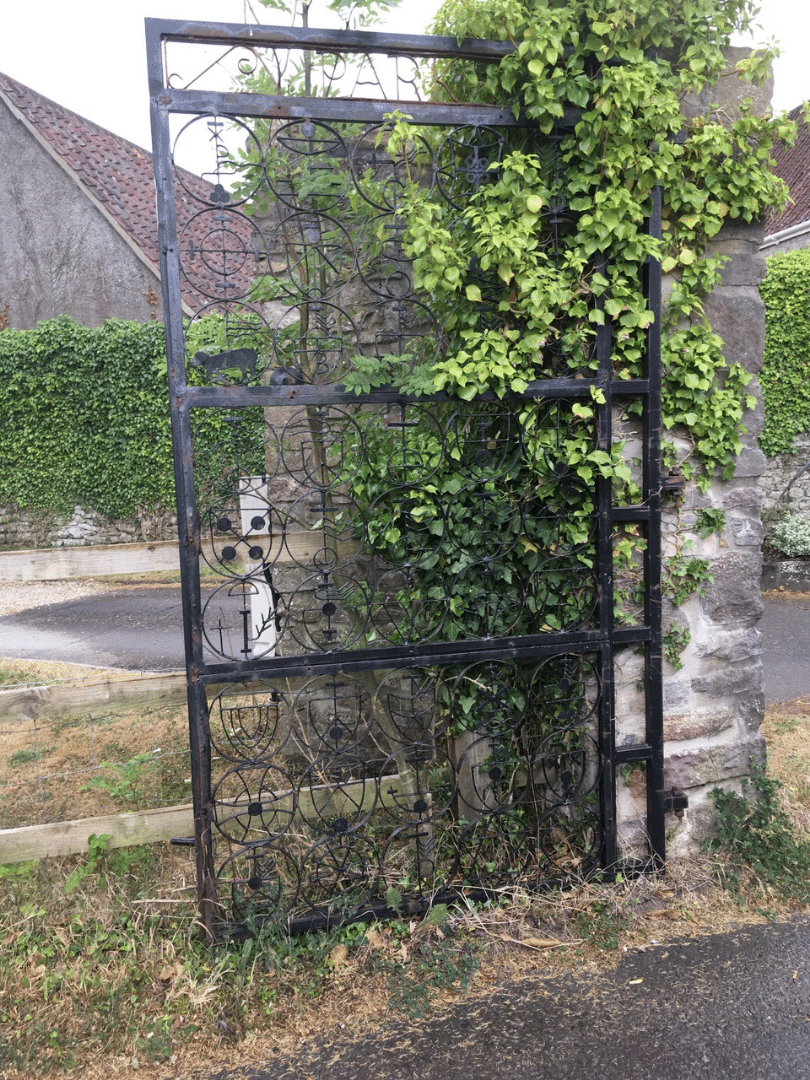

At the end of Church Road in Abbots Leigh, a gateway leads into a private lane. The gates are pushed open, so it’s not surprising that from the road you can’t see what’s hidden there. But walking just past the gate posts, wrought iron gates on either side mark the entrance to South Down Park. It takes more than a cursory look to see that these double gates incorporate, not a repeating pattern often used for wrought-iron work, but ninety distinct emblems.

At first glance they resemble printers’ marks, a device or logo used since the middle of the fifteenth century as trademarks for printers. These devices, often included on the title page of a book, can help identify the printer, the city, and a possible date for any early printed book. In the twenty-first century, publishers still use these marks, now mostly as decorative elements on a book’s spine and title page.

There was no significant printing industry in Bristol, not one that would account for ninety emblems, but there were merchants. Printers marks no doubt derive from merchant marks, which date back to Mesopotamia in the third millennium BCE. As part of the administration of trade, these marks were stamped onto cloth or sealing wax and attached to merchandise to identify the owner. These marks were used in the West during the Middle Ages for the same purpose. Could these gates incorporate Bristol Merchant Marks? And if they do, where did the gates come from and how did they find their way to Abbots Leigh?

First conjectures were that the gates came from an old Bristol building, perhaps even the Old Guild Hall. During World War II, they might have been requisitioned but proving to be unusable, ended up in a scrap yard. Simon Talbot-Ponsonby identified the man who installed those gates in about 1980 as Mr. Terry Bryant, who acquired the property at South Down Park. Perhaps he retrieved the panels to incorporate them into gates. Mr. Bryant, a house builder with a particular interest in Bristol memorabilia, may have recognised what these panels represented.

In an attempt to discover where these panels might have been before coming to Abbots Leigh, emails went out to the Clifton Antiquarian Club, the Clifton and Hotwells Improvement Society, the Society of Merchant Venturers and collectors of photographs of Old Bristol without result. The Facebook Group, “Bristol Now and Then,” with 5,800 members, also could not identify the panels.

Discovering the actual source for the panels changed the theory about Mr. Bryant finding the gates in a scrap yard. On January 12, 1911, Alfred E. Hudd, Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London and Honorary Secretary of the Clifton Antiquarian Club, read a paper to that club on Bristol Merchant Marks. It was subsequently printed in the Club’s Proceedings, Volume 7, Part 2, 1910–11. Although the Proceedings are available at the Bristol Central Library, the Covid-19 lockdown made them inaccessible, but a reprint house in India could provide print-on-demand copies of the article. After waiting six weeks for the article to arrive, the seller admitted that because of Covid-19 he was finding it difficult to ship anything. He graciously sent a digital copy1.

The article offered an extensive study of Bristol Merchant Marks, but more importantly, it also included drawings of 485 marks with details about each of the merchants, as well as ecclesiastics, church wardens, and others who used such marks. Mr. Hudd examined tombstones and sepulchral monuments, stained glass windows, building decoration, portraits, signet rings, silver plate, pottery, drawings, deeds, and church books to connect Bristolians with their marks.

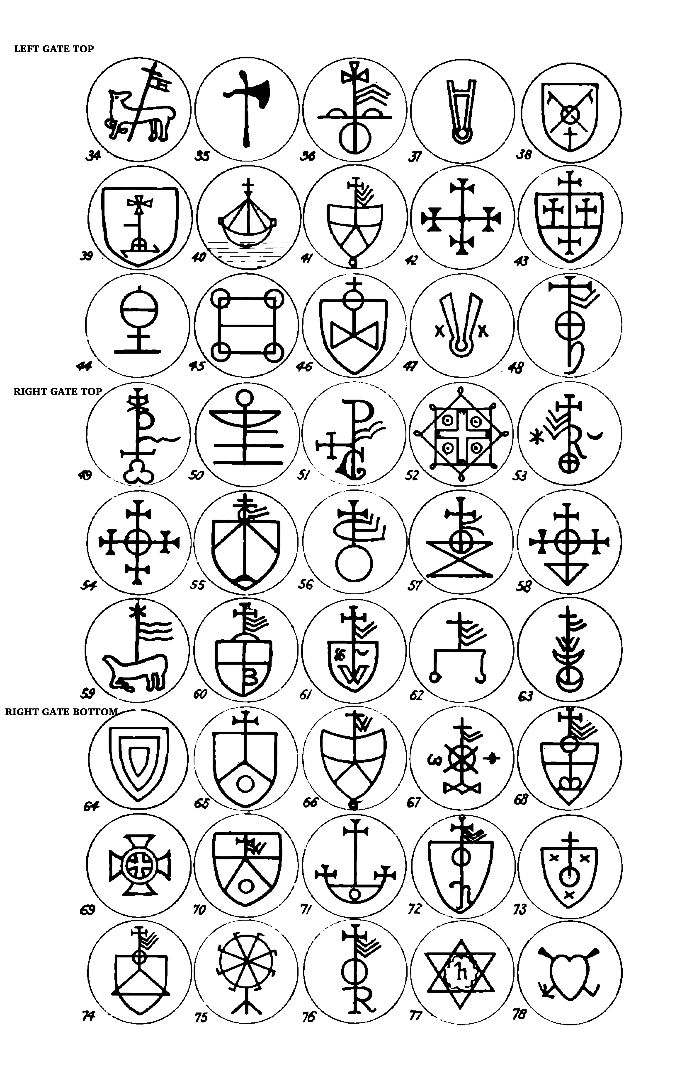

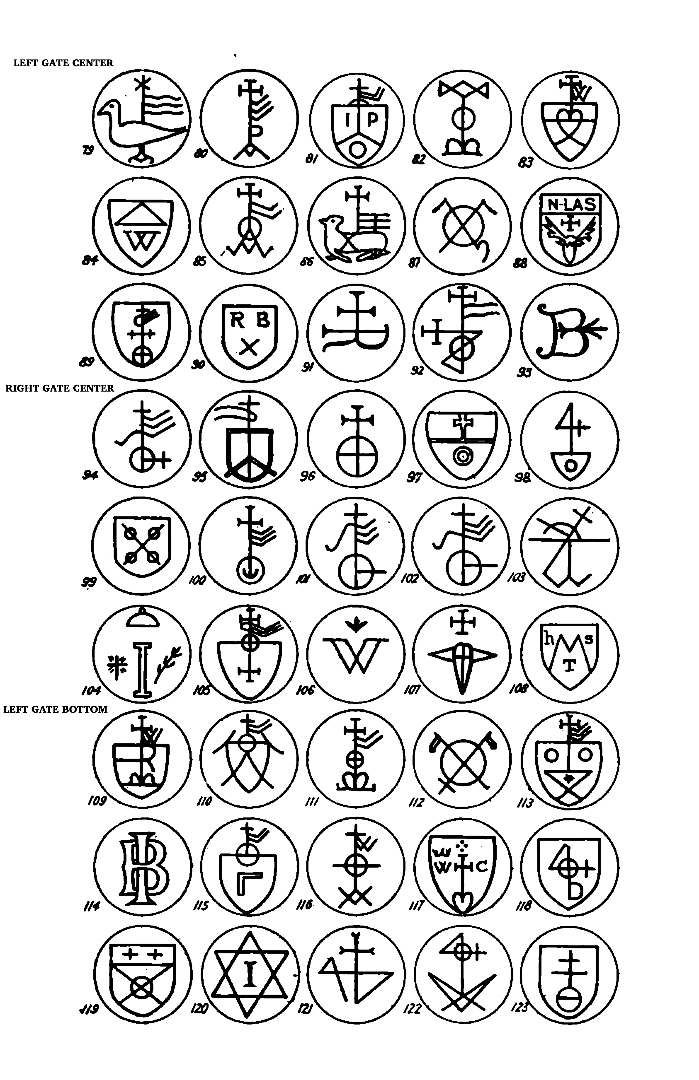

Each of the two South Down Park gates comprise three panels of fifteen marks, with each set of fifteen corresponding exactly with Mr. Hudd’s marks no. 34 to 123. They begin on the top of the left gate with the seal of Agnes le Chamberlain from a deed to property in Henbury Parish dated 1326 and conclude at the bottom of the right gate with a deed dated August 11th, 1362, with Philip le Long, burgess of Bristol, and Thomas Denebawe granting to Adam Pountfreit a house and land called “le Erbe” in “Seynt Colastret,” which was in the area between St. Nicholas’ Gate and St. Leonard’s Gate. The entire key can be downloaded here.

The emblems on the gates are clearly based on Mr. Hudd’s original research and the drawings that accompanied his article, so the panels can date from no earlier than 1911. Furthermore, Andy Theale of Iron Art of Bath, which restores heritage wrought and cast iron, looked at photos of the South Down Park gates and identified them as “thoroughly modern.” They are the product of electric welding, which was not used until after World War I but doesn’t seem to have come into widespread use until the middle of the twentieth century.

The design of the gates is based on pages two and three of eleven pages of seals illustrated in Mr. Hudd’s article. The designer probably passed over page one, because it lacks the symmetricity of the other pages, reproducing with four larger lozenge-shaped seals, only thirty-three rather than forty-five marks. The panels were not incorporated into the gates in the sequence in which they appeared in print, but follow top left, top right, bottom right, centre left, centre right, bottom left. Whereas the article included marks from as late as 1653, the selected marks are among the earliest reproduced by Mr. Hudd, dating from the fourteenth century. The marks were apparently selected simply as historical design elements without any particular interest in the individuals who owned them.

Unless someone recognises these gates from an earlier site, it is most likely that Mr. Bryant, with his interest in Bristol history, designed the gates based on Mr. Hudd’s article and had them especially made for South Down Park.

1This document is too large to be uploaded but is available on application to the Webmaster.

POSTSCRIPT

John Winstone, retired chartered specialist conservation architect, comments:

These appear to me to be post-WWII, wanting somewhat in good detailing, but of interesting design. The mason's marks are clearly a reconstruction of Alfred Hudd's early C20 article in the Proceedings of the Clifton Archaeological Club. Notice of Terry Bryant's name as owner of South Down Park (rather than Southdown Park) was sufficient for me to ascribe the choice of the merchant's emblems to Terry's own interest in Bristol History. I first came across Terry's name through his connection with my father, Reece Winstone, and later I visited Terry at his subsequent home in Ravenshill Road, Knowle. He was interested in Bristol makers of optical instruments and was collecting information for a monograph. We had a C19 trade card of a Bristol instrument maker and were about to publish it in Bristol Trade Cards (1993 - volume 39 of a series), where TB's help is acknowledged.

Terry was the eldest son of a family of Bristol speculative house-builders. He had a falling out with his fellow directors; I believe over adverse publicity springing from his views of the City Council's port expansion. If this resulted in a set back for Terry, he bore it well. He had managed to build a personal collection of Bristol books and manuscripts which he marked with a roundel 'Terence Bryant Collection' by rubber stamp in green ink.

I cannot tell from the photographs to what extent Terry may have worked on the stone gate piers. As to the conservation of the gates, they are certainly worthy of designation as a locally listed asset, provided they remain in situ in their designed location, and should be put in good repair.